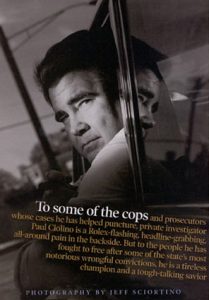

by Bryan Smith

Chicago magazine July 2002

Jagoffs. He’s surrounded by friggin’ jagoffs. Cops. Clients. Lawyers. Especially lawyers, he thinks. Jesus. You investigate something for those guys, flipping over every sad sack’s sorry-ass story; doing everything but tying up the case for them with a pretty bow and what does it get you? It gets you behind the wheel on a freezing Wednesday night, driving 40 miles in a snowstorm, trying to track down some crazy old broad who reads something about your client in the paper; and now she claims she overheard him say something incriminating. And it’s not just any client. It’s John frigging Carroccia, the guy accused of killing a small-town cop, Greg Sears —the same cop who happened to be Carroccia’s best friend. All of which instantly made this case a redball murder that everyone and his brother were trying to make their chops on.

Jagoffs. He’s surrounded by friggin’ jagoffs. Cops. Clients. Lawyers. Especially lawyers, he thinks. Jesus. You investigate something for those guys, flipping over every sad sack’s sorry-ass story; doing everything but tying up the case for them with a pretty bow and what does it get you? It gets you behind the wheel on a freezing Wednesday night, driving 40 miles in a snowstorm, trying to track down some crazy old broad who reads something about your client in the paper; and now she claims she overheard him say something incriminating. And it’s not just any client. It’s John frigging Carroccia, the guy accused of killing a small-town cop, Greg Sears —the same cop who happened to be Carroccia’s best friend. All of which instantly made this case a redball murder that everyone and his brother were trying to make their chops on.

So here he is: skidding around the corner of some bumfrig town, rolling the bones that this lady is actually home, and seeing that her house is darker than a cop’s face at a closed doughnut shop. He snaps on a dome light and reads the report. She’d been at her department store job when she saw someone who looked like the accused talking to someone who looked like the dead cop, and she says she overheard a threat. He pulls a fleshy paw over his face. The prosecutors probably won’t even call her as a witness. But he has to check it out, because in the private eye business this is what he does.

“All right,” he says, throwing open the car door; tossing the stub of a Swisher Sweet cigar into the snow with a sizzle. “Let’s see what this crazy broad heard.” He crunches through the snow and heads around back, looking for a Fido tray and a chain. “Dogs don’t like private investigators,” he explains. He glances up and practically stumbles over a garden statue of the Virgin Mary “That don’t go too well with private investigation, either.”

Two sharp raps bring nothing-no sounds, no lights. “She ain’t here,” he grumbles, giving the house his back. “Forty miles and Granny ain’t home.”

Two sharp raps bring nothing-no sounds, no lights. “She ain’t here,” he grumbles, giving the house his back. “Forty miles and Granny ain’t home.”

Such is his life: Bust your hump to prove someone’s banging someone else’s old lady, or to finger some businessman who’s padding his account, or to discredit some bimbo’s paternity claim. Or you drive 40 miles in a snowstorm for someone who’s not there. It’s days like this that he looks in the mirror and asks the weary face staring back, Who needs this shit?

It’s also such days when Paul Ciolino, private dick, smirks a little to himself, jams the keys into his Mercedes, and cranks up the Bobby Darin CD. Who is he kidding? He has the best job in the world. Is there anything like that sweet feeling of beating the government’s ass on a wrongful conviction, or springing an innocent guy like Carroccia? Surfing the adrenaline buzz of pulling off the impossible, knowing the cops hated you for it, but not caring because you know you are doing the right thing?

Who needs it? Friggin’ A. He does.

At 46, Paul Ciolino is big and loud.To some people – many of the cops and prosecutors he has gone up against, for example – he’s a grandstanding blowhard. But Ciolino is also one of Chicago’s most successful, most visible, most sought-alter private investigators, a $150-an-hour tough-talking savior to people caught in the worst kinds of jams. Working out of his downtown and Palatine offices, he has built a small empire on the standard trenchcoat-and-fedora fare of the P.I.: digging out those dirty little secrets that like to hide in the dark comers of suburban bliss. Swisher Sweet clamped between his teeth, a cashmere topcoat draped on his shoulders, he strides the Chicago region as a giant pain in the ass to those he has been hired to find, fluster; or expose.

But beyond the Mike Hammer act, Ciolino has also been a force in some of the biggest wrongful conviction cases in Illinois, and he can legitimately lay claim to helping win the state’s current death penalty moratorium. His notoriety started in 1988 with the case of Sandra Fabiano, accused of molesting children at her Mother Goose Pre-School in Palos Hills. Ciolino began investigating amid news reports that looked bleak for Fabiano. By the end, he’d dug up so much stuff damaging to the prosecution’s case that the acquittal was almost a foregone conclusion.

Teaming with Northwestern University journalism professor David Protess, he helped win the freedom in 1996 of the “Ford Heights Four,” four African American men convicted in the 1978 murders of a south suburban couple. And most recently, he almost single-handedly saved Anthony Porter; who at one point was two days from being executed for the 1982 murders of a man and a woman in Washington Park In that case, which Protess and his students also investigated, Ciolino got the real killer to confess on video after tracking him down in Milwaukee.

By last year; Ciolino was regularly being called upon to investigate death penalty convictions that appeared shaky He worked with Andrea Lyon, director of the Center for Justice in Capital Cases at DePaul University College of Law, and Terence MacCarthy, executive director of the Federal Defender Program in Chicago, which provides lawyers to indigent people charged with federal crimes. He teamed with Herb Wells, a private investigator in Mississippi, to try to clear a man Ciolino believes was wrongfully arrested m a double homicide. Shows such as 60 Minutes and 48 Hours began calling. Last summer, when congressional intern Chandra Levy disappeared, Ciolino popped up on TV as an expert.

Along the way, Ciolino developed a reputation as a tough, sometimes pushy, slightly over-the-top hall buster who, whether you liked him or not, was the person you would most want investigating your case, particularly if you were sitting in a jail cell charged with something that could land you on death row.

“Yes, he can he a little overheating, but in these kinds of cases you want someone aggressive,” says defense attorney Jack Rimland. “I’ve seen him do some stuff that was just phenomenal – getting people to fess up, getting people exonerated.”

Now Ciolino is trying to get a guy off who was accused of killing a cop – a well-liked cop from little Marengo, Illinois. John Carroccia was arrested on June 2, 2000, one day after the body of Greg Sears was found facedown, with three execution-style rounds from a .38 in his head. The police had a witness who placed someone at the scene fitting Carroccia’s build and who also claimed he had seen a van resembling Carroccia’s being driven away that night. Carroccia and Sears had been best buddies, but Sears’s widow, Norma Jean, said their friendship had cooled after she married Sears. The case was far from a slam dunk for the state, however. The prosecution didn’t have a firm motive, and the eyewitness testimony was questionable, at best. The cops had not found a murder weapon, and questions were raised about the credibility of Norma Jean Sears. Besides, there was no physical evidence tying Carroccia to the murder.

Even so, fighting a cop-killing charge is a defender’s worst nightmare. Prosecutors and police feel pressured to solve the case quickly, and they’re usually given a blank check to get it done. Jurors are known to give the government the benefit of the doubt in such cases.

Ciolino has his work cut out for him. He starts by tracking down an expert who can map out the murder scene. What were the conditions like that night? Could the main witness really have seen what he said he saw? Next, he considers Carroccia’s alibi. Is it solid? Then he begins looking for someone other than Carroccia who might have had the motive to kill the officer. And since you always turn to the wife, he starts looking at the widow.

I t’s a chill mid-February morning, and Paul Ciolino is a wreck.Or at least his office is – devastated by a flood from a busted sump pump that has caused $60,000 to $80,000 in damage: Worse, he has only recently moved to this Palatine location-a stand-alone office wedged between low-slung shops like Judy’s Quilt and Sew and Allanna’s Beauty Botique. His desk, an $8,000 custom-made conference table the size of a sun deck, is heaped with legal pads and old newspaper articles. A tin of Altoids shares space with a “What a Guy” mug. Cigar stubs spill from an ashtray choked with the cinders of the three boxes of Swishers he goes through each day. “I’ve been a train wreck, organization-wise,” Ciolino growls. “Pain in the ass. It would be a great business if it wasn’t for clients, buildings, and employees.”

From behind the pile and the swirl of cigar smoke, he looks lost. He swills a Diet Coke and yanks up the phone, trying to get through to a lawyer. The lawyer’s new secretary hassles him. Big mistake. “This is Paul from Chicago, honey,” he says. “Tell him when I call it’s like the Lord calling.” He cups his hand over the receiver. “New secretary every week. I end up having to straighten out these broads.”

He dispatches the lawyer and takes a call-Ronald Kliner, checking in daily from death row. “Hey Ron. What do you want, man? I’m busy.” Kliner was convicted in the 1988contract killing of Dana Rinaldi, a woman from Palatine Township murdered at the behest of her husband, the authorities say. Kliner is one of Ciolino’s latest causes – and, Ciolino believes, one of his next big wrongful conviction scores. Ciolino insists that Kliner has an airtight alibi. The private eye has written letters to Governor Ryan for Kliner. He even argued in an October 2000 hearing that Kliner should be pardoned. “I put on a show,” Ciolino confided in an earlier discussion of the case. “I tell you what, though. I go to bed thinking about Ron KIiner. I wake up thinking about Ron Kliner – and about six or seven others who I know shouldn’t be where they’re at.”

“What is it?” Ciolino now says into the phone. “I know. I know. Well, I’m glad you’re so smart. That’s why you’re sitting where you’re at and I’m sitting where I’m at. Listen, there’d be nothing better for me than you to walk out on my petition [for a pardon]. All right brother.”

Ciolino bangs the phone down and shakes his head. “I believe with all my heart that he did not commit that crime,” he says. “But he comes off as such an asshole. He doesn’t make it easy”

Ciolino may grab headlines by getting people off death row – mostly on his own dime – but he is no one’s picture of a liberal crusader: Six feet two inches tall, 250 pounds, with the flat accent of the South Side, he wears good wool suits – $1,500 a pop from Dei Giovani at Wells and Madison. On his wrist gleams a gold Rolex Presidential. He drives a slut-red Mercedes SL500 – $106,000 new – and a silver Rolls-Royce he bought off eBay after a particularly lucrative case. When he talks, he swears like a cop, and he keeps enough guns in the coffin-size safe behind his desk to make Charlton Heston giddy. When he enters a room it is with the force of a hammer: shoulders back, hair frozen into a blow-dried helmet -part Tony Soprano, part Andy Sipowicz, part Wayne Newton.

“He appears to be a very tough guy,” says Andrea Lyon, of DePaul’s Center for Justice in Capital Cases, one of the nation’s most respected death penalty foes. “You have to look a little deeper.”

Ciolino seems amused with how he is perceived. “Five years ago I was just another crazy investigator,” he says. “Now I’m some kind of death penalty guru.”

His clients and supporters read like a who’s who of anti-death penalty liberals: Stephen Bright of the Southern Center for Human Rights; the Federal Defender Program’s Terence MacCarthy; Stephen Baker, public defender for DuPage County; Professor Protess; the NAACP in Texas.

Just recently in Starkville, Mississippi, Ciolino stood in front of local TV cameras, cheered on by a crowd of 200 African American townspeople. He had taken on the local sheriff in the case of a young black man arrested for a double homicide. The accused man, Rondez Harris, had been a childhood friend of one of the victims, and the sheriff focused on Harris right away. “We toasted their ass on the total lack of physical evidence, witnesses, confessions,” Ciolino says. “I told the sheriff, ‘If you don’t drop these charges I’m going to torture you in the media.’ So I held a press conference with every station in town.”

Such stunts have been effective, but they have also earned Ciolino powerful enemies. State’s attorneys and police don’t like to have their convictions overturned – and don’t like to see a big, loudmouthed slab of beef in a cashmere coat barking on every 10p.m. newscast, calling them stupid, incompetent, and worse. In the Fabiano case, Ciolino said the prosecutor should have been “horsewhipped.” In the Porter case, he said the police were the ones who should have been locked up.

“He definitely says things I would never say,” explains Steve Kirby, also a Chicago-area private investigator. “There’s a lot of people who don’t like his style.”

Ciolino has been threatened with subpoenas and indictments more times than he can count by people who make their living finding reasons to throw people in jail. As a result, he knows he has to do everything by the book.

He danced close to the edge in the Porter case in getting Alistory Simon, the suspected real killer, to confess to the murder.

Showing up unannounced at Simon’s house in Milwaukee, Ciolino said that he was a private investigator and that he bad a videotape of a witness who said Simon had committed the Washington Park murders. The “witness” was actually an employee of Ciolino’s. Watching the bogus video, Simon remarked, “Man, that guy wasn’t there. He ain’t no witness.”

‘Yeah?” Ciolino shot back. “How do you know that if you weren’t there?” A~ that point, recalls Ciolino, “he looked at me like, ‘Why did I open my mouth?”‘ Afterwards, Ciolino convinced Simon that if he confessed on tape, things would go easier for him. “We just bull-rushed him, and mentally he couldn’t recover,” Ciolino says.

The scam set off alarm bells with some people. “I took big heat from journalists,” Ciolino says. “I could not explain to these knuckleheads that I’m not a friggin’ journalist, OK? I had [an Associated Press] writer barbecue me, man. She calls up the state’s attorney [Thomas Gainer], and he gets cute and says, ‘Well, we gotta examine the methods that were used.’ Them mofos. They beat you over the head with the yellow pages, and they’re talking about examining me? Nothing happened.” (A point on style: rather than using terms like “friggin”‘ and “mofo,” Ciolino uses more pungent language. But you get the idea.)

Gainer, now a Cook County judge, declined to comment for this article.

“They hate me,” Ciolino says of prosecutors and cops. “They would like’ nothing better than for me to go away. I understand that, but it’s tough shit. I got plenty of friends. I don’t need any more friends.”

So he doesn’t mind offending people?

“I’m in the offending business,” he says.

A solid case? My ass, Ciolino thinks. They shouldn’t have charged John Carroccia and they know it. What did they have? He was best friends with the dead cop. So what? The two liked to hang out. Big friggin’ deal. Carroccia collects guns. Who doesn’t in them small towns? The dead cop’s widow has a pretty big collection, and she wasn’t rotting in jail.

On the other hand, Carroccia’s alibi is not great. That’s a problem. He told the cops he was at home watching Frasier. But he also said he was out buying a special kind of oil for his van. Well, he could have done both. He was a single guy. That’s what single guys do – watch TV and get motor oil. The lawyers would have to make that work.

The motive? A joke. Trying to make some big deal out of an argument Carroccia supposedly had with Greg Sears over the time Sears was spending with his new wife. That argument was planted in the cops’ minds by the same woman who brought Carroccia’s name up in the first place: Norma Jean Sears. And the witnesses – well, we’ll just see how well their stories stand up.

Meanwhile, Carroccia is out on bond – and he’s losing it. Calling every day. Worrying everything to death. Listen, Ciolino tells him. I’m all over this case and they ain’t sending you to friggin’ prison. You’re walking out of there a free man, all right?

Paul Ciolino has always been determined. All the way back to when he was still cutting his chops doing background checks and chasing cheating spouses. Those were good times – plenty of clients, plenty of work. When be hired a street-smart, no bull assistant with a heart of gold named-what else? – Grace, it was as if he had come off the set of a private eye thriller and set up shop in the perfect tough guy town. He worked cases right out of True Detective, full of sad vice and petty indiscretion.

At first, Ciolino struggled to keep the lights on, but when he started doing government and corporate work – background checks, process serving, chasing down fraud – his business took off He began to accumulate toys – the Mercedes, a giant-screen TV a sound system that cost more than his father had made in a year.

It was a good life, an unlikely life, for the big kid from 95th and Green who had gotten married at 16, had a child at 17, and had to work through high school to support a family. He grew up on the South Side, devouring novels by Zane Grey and, yes, Mickey Spillane, covering his ears when his parents screamed at each other and ducking backhands from his father “My dad was a city guy, born and raised at 24th and Wentworth,” he says. “A car salesman. Talk about a brutal business – and my old man was good at it.”

Ciolino learned two things: to move quickly and never to become a car salesman. Instead, after he got his girlfriend pregnant, he found himself bagging gravel on a loading dock at Goldblatt’s. “There was no mercy,” he says. “They didn’t care if you were 16 or 65: ‘Get out there and unload that boxcar fall of gravel bags.’ And you haven’t lived until you’ve unloaded a 60-foot boxcar of 50-pound bags of decorative gravel by yourself. Wreck your back, you go see the doctor down the street, who probably didn’t have a license. Pumps you fall of painkillers and sends you back to work.”

Ciolino joined the army right after finishing high school. Started out in the infantry moved up to MP and then to investigations, working at bases in Germany and at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. But he soon got sick of busting soldiers who “were 20 years old, cock strong, and mean.” He got out after seven years, a 24-year old who had seen it all. He thought about becoming a cop, but he’d had plenty of that in the army Besides, he says, “I’m not real good at taking orders from idiots, and police departments are full of idiots.”

He started attending Moraine Valley Junior College until one day his father introduced him to a customer: a private detective who worked for Al DiLuigi, a hard-boiled egg who ran a P.I. business in the city. “I didn’t know what a private investigator was,” Ciolino recalls. “You think you’re going to be out there like Mike Hammer, shooting people in the street with your .45,”‘

DiLuigi taught him what it was really about: 16-hour days and writing up reports; all-night stakeouts and Christmas Eve in sleazy, out-of-town hotel bars. “He was a prick all the way,” Ciolino says. “‘Go make me money and catch the mofo,’ was what he used to tell me. ‘Until then, don’t bother me.’ But I learned,”

Enough to open his own agency in March1988. Over the years, he developed techniques, like taking a court reporter onto the streets with a portable dictation machine, having her set up and take a statement right on the corner if need be. Most of all, he learned enough to listen one day years later, when he was at dinner with a professor he had met, David Protess, and a smart journalist, Rob Warden. At the time, “no one was more for the death penalty’ than I was,” Ciolino recalls. “I was always of the opinion that evil mofos should be removed from the face of the earth. For the first time in my life, two people who were really familiar with the situation, and who had some serious brain power, started laying it out for me. I’m going, Well, I better reconsider my thinking.”

By the time the two were through with him, he had completely changed his mind. Today he ticks off a litany of reasons why he thinks the death penalty is wrong. “One, it’s generally racist. Two, it’s used as a political tool and headline grabber. Three, it’s ineffective – it doesn’t deter crime. Four, life in prison is far more effective [as a deterrent] and miserable.”

In 1995, Ciolino began working with Protess, who ran an investigative journalism course at Northwestern. Each semester, he’d assign his students cases – some of them death row convictions – and tell them to reinvestigate. If the person had been found guilty the students were to determine the validity of that verdict. In a few cases, after investigating, the students believed the prisoner was innocent and then looked for holes in the trial that might help the case get overturned.

Behind the scenes, the real work was done by Protess and Ciolino – especially Ciolino – but the media lapped up the story of the student “Angels of Death Row,” as one headline put it. Ciolino played along with the fairy tale, but it bugged him. Yes, the students did their part. They went into rough neighborhoods – after a “Ghetto 101” course from Ciolino. Yes, they tracked down leads. But when the newspaper stories came out praising only them, he couldn’t help it, he says: He was pissed.

“Paul Ciolino was the unsung hero,” Protess acknowledges. “He got the confession that turned the Porter case around. There’s no doubt we got too much credit in that case, Protess says, and on just about every other that involved Ciolino and the students.

“I sat there and talked to a New York Times reporter for an hour about the Porter case,” Ciolino grumbles. “When [the article] came out, I didn’t exist.”

True, perhaps. Still, it is a little unseemly for Ciolino to complain about the media. He knows the rules, and he manipulates them better than most. He pals up reporters, feeding them juicy bits, playing favorites, even using them as references on his resume. In cases of wrongful conviction, he makes sure he’s there all along the way, calling up reporters from time to time to “see how it’s going,” shaping the story.

He’s hard to resist. After all, he comes through with the goods. And he’s fun to be around. “He takes on the cases we all care about, and he takes them on with a passion that is just so addictive and inspiring,” says Erin Moriarty; a correspondent with CBS’s 48 Hours who has worked with Ciolino on several cases.

As for media attention, he can ,hardly claim he has been ignored. He has appeared on 48 Hours. And he has “consulted” on and “managed” (in his words, on his resume) investigations for 60 Minutes, Inside Edition, 20/20, Dateline NBC, and CNN’s Burden of Proof.

Indeed, his detractors think he is all too enamored of the press.

“Normally you don’t see an investigator making these kinds of comments” on television, says Robert Berlin, the Kane County prosecutor on the Carroccia case. “But the guy wants press.”

“He uses the media, which we all do to some extent,” adds Ciolino’s friend Steve Kirby. “But some of his self-promotion gets a little old. He’s very bombastic, so people either like him or they don’t.”

Friggin’ juries, Ciolino thinks. Put 12 people in a room and anything can happen. Well, either way, it’s out of his hands, now. His work is done – the digging part, anyway. Now it’s about holding hands. Making sure Carroccia doesn’t freak out. Making sure the lawyers have what they need. Schmoozing reporters. The usual.

And with Carroccia, the digging has been good. A little basic investigative work has revealed that the murder scene was 475 feet from the loading dock where the witnesses were standing – a long way for anyone to see. A heavy rainstorm had moved through at the time of the shooting, farther reducing visibility; and a streetlight had been knocked out during the storm, rendering the area almost pitch dark.

Ciolino has learned that a speck of blood found on Carroccia’s pants – a discovery initially ballyhooed by investigators – belonged to Carroccia himself, and none of the victim’s blood had been found on Carroccia or in his van.

Ciolino gave Carroccia’s lawyer; Stephen Komie, the material with which to. impeach the state’s star witness – the only person to put someone fitting Carroccia’s description at the scene of the crime – by digging up his record of domestic battery and the fact that he had been a paid informant far the state in the past. Ciolino also found information about the widow of the slain officer – she had once been fired for lying, had also faked her own kidnapping, and, in the days leading up to the murder, had called a male friend in Florida dozens of times – and records of these incidents were introduced to the judge.

Of course, much of his investigation led to dead ends. He never did find the woman whose house he visited that snowy night, but he had turned out to be right about her: The prosecutors never called her as a witness, Also, the judge in the case excluded much of what Ciolino found, particularly that information about Sears’s widow, which was inadmissible because none of the incidents resulted in any felony convictions. But many of those details found their way into newspaper and TV stories – including one by this reporter – before the trial, shaping perceptions about the case. Defense lawyers were also able to slip in some of the information in the questions they asked.

In short, Ciolino was able to do what a good private dick does generally, and what he does specifically: drive the other side crazy. “He was very thorough,” admitted Robert Berlin, the prosecutor on the case.

The jury deliberating John Carroccia’s fate returns a verdict in two hours: not guilty.The jurors say afterwards that the defense hadn’t even needed to put on a case.

On a chilly night in Marengo, Carroccia family members celebrate in the basement of their home. The bright lights of a TV camera burn, swinging through the room. Carroccia, exhausted, throws his arms around anyone near him. When Ciolino finally arrives, camel topcoat flung over his, shoulders, Swisher between his teeth, voice booming, the sea of guests parts for the Big Man. Carroccia’s family and friends clap him on the back, some with tears in their eyes. For a moment, Ciolino actually looks restrained. And when he returns the hugs and handshakes, it is with the smile of a genuine friend.

But the sensitive-guy routine can last only so long. Earlier, after the verdict came in, Steve Kirby had warned his pal to “be humble, be gracious.”

Yeah, OK, Steve, he thinks. Just ripped the government a new one, and I’m going to be humble and gracious? Screw it.

He could already see how it was going to go: friggin’ lawyers holding a press conference, getting all the credit. Friggin’ media, looking at him like he was some kind of jagoff. Be a great job if it weren’t for clients, lawyers, and the media.

Frig it. Tomorrow he is already back to another case: a guy named Oily charged with a murder Ciolino is convinced he didn’t do. A whole new set of headaches.

Probably get another death row call from Kliner. And there was one call he’d be glad to return: Some Hollywood producer said he wanted to meet with Ciolino to talk about turning his life into a TV series. It wasn’t the first time L.A. had come nibbling, but, hey, he’d take their ticket and go sit by the pool. Who knew? Maybe something would actually come out of it. The Big Man in Hollywood. Yeah, he could see it. Hanging on the set with them Hollywood broads, watching his life play in front of the cameras. The Death Penalty Guru. Enemy of the State.

But talk about your jagoffs. Producers? Directors? Who needed that shit?

Friggin’ A.